This week is an introduction to CAD (Computer-Aided Design), where we model in both 2D and 3D. I explored different design approaches using raster-based, vector-based, and 3D modeling software, learning how each tool serves a different purpose in the design-to-fabrication workflow. I also learned about parametric design concepts, constraints, and user parameters, which are important fundamentals of Computer Aided Design. You can access my design files at the bottom of the page.

Learning Objectives

- Evaluate and select 2D and 3D software

- Demonstrate and describe processes used in modelling with 2D and 3D software

- Demonstrate image and video compression

Hero Shot

2D Design

To model in 2D, you can use either a raster-based program or a vector-based program, depending on the purpose of the design stage.

In a raster program, we work with a grid of pixels where each pixel has color and transparency information. Raster tools are well suited for visual design and layout exploration, but they are not ideal for fabrication because they do not preserve geometric accuracy when scaled. My raster program of choice was Adobe Photoshop, as it allowed fast visual iteration and freedom while designing the screen interface and overall layout.

In a vector program, shapes are defined using mathematical paths instead of pixels. This allows designs to be scaled without any loss of quality, making vector tools more suitable for fabrication workflows. My vector program of choice was Adobe Illustrator, since it provides precise control over geometry and can directly export machine-ready file formats.

So very basically, raster programs work with pixels, while vector programs work with mathematical calculations.

Raster Based

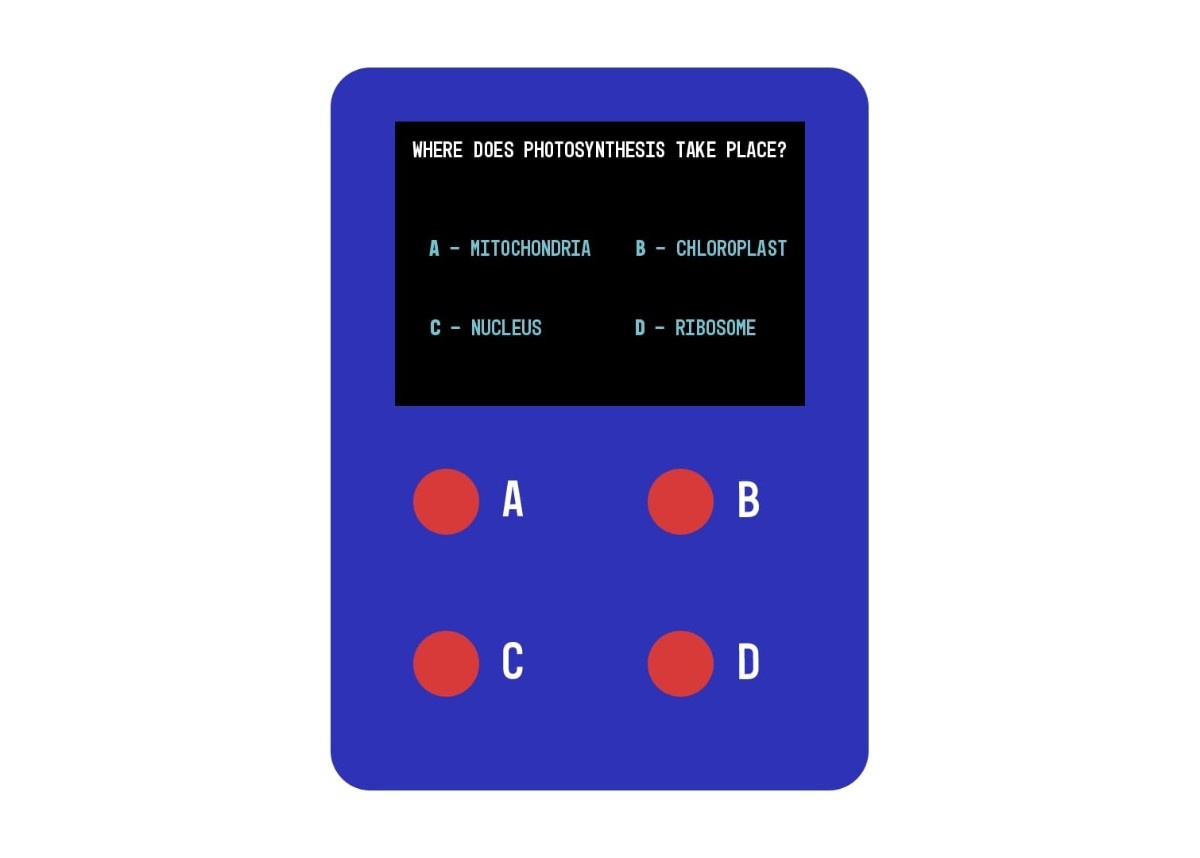

I used the raster-based workflow to focus on the visual design and layout planning of my device, which includes a screen and four buttons. In Adobe Photoshop, I created a conceptual user interface for the screen and explored the proportions and placement of components. This helped guide later fabrication-oriented design decisions without being restricted by exact dimensions.

Note: This design is exported in .jpg format and is not intended for fabrication. It is only used to sketch and plan the device’s layout.

Below you can see my final design made in Adobe Photoshop:

Vector Based

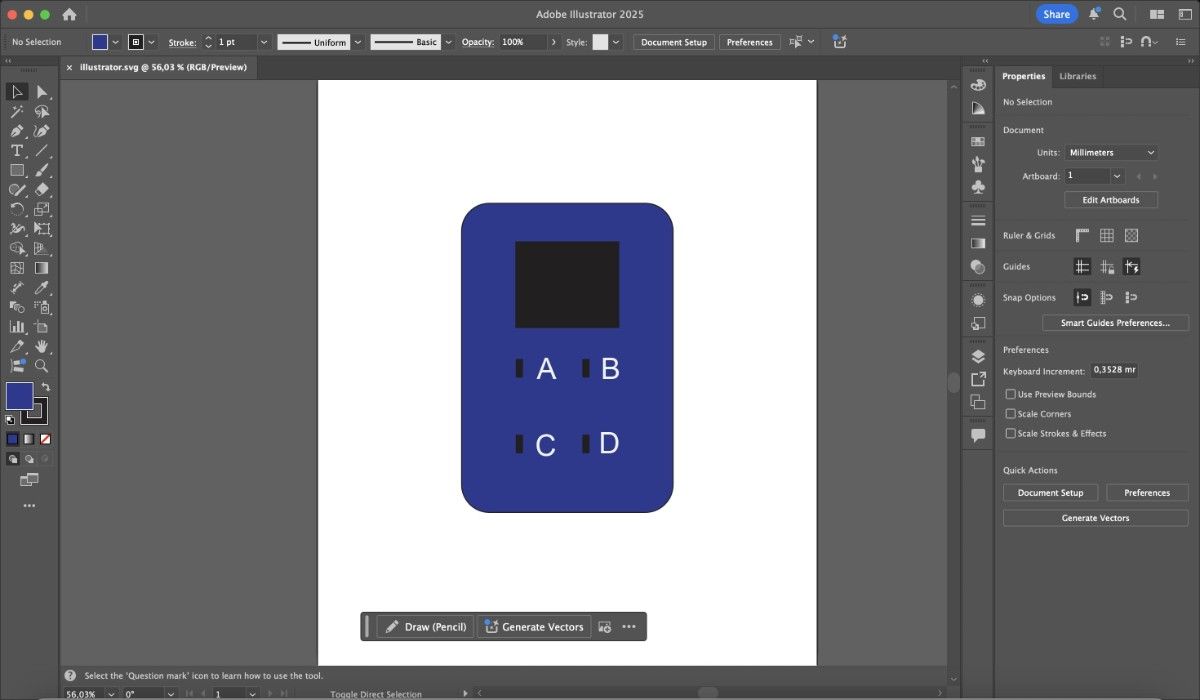

I used the vector-based workflow to create a design that could later be exported in .svg format and fabricated. This file format is important because it can be directly used with laser cutters. Working in a vector environment helped me understand how fabrication-oriented design differs from purely visual design, as all geometry must be intentional and dimensionally meaningful.

The vector design includes cutouts for the screen and buttons, making it suitable for physical production. Vector-based programs also rely heavily on boolean operations such as union, difference, and intersection, which are commonly used when preparing files for digital fabrication.

Note: Vector-based 2D geometry can be created inside 3D CAD software, but dedicated vector tools are often more efficient for producing clean, fabrication-ready 2D files.

Below you can see my final design made in Adobe Illustrator:

3D Modelling

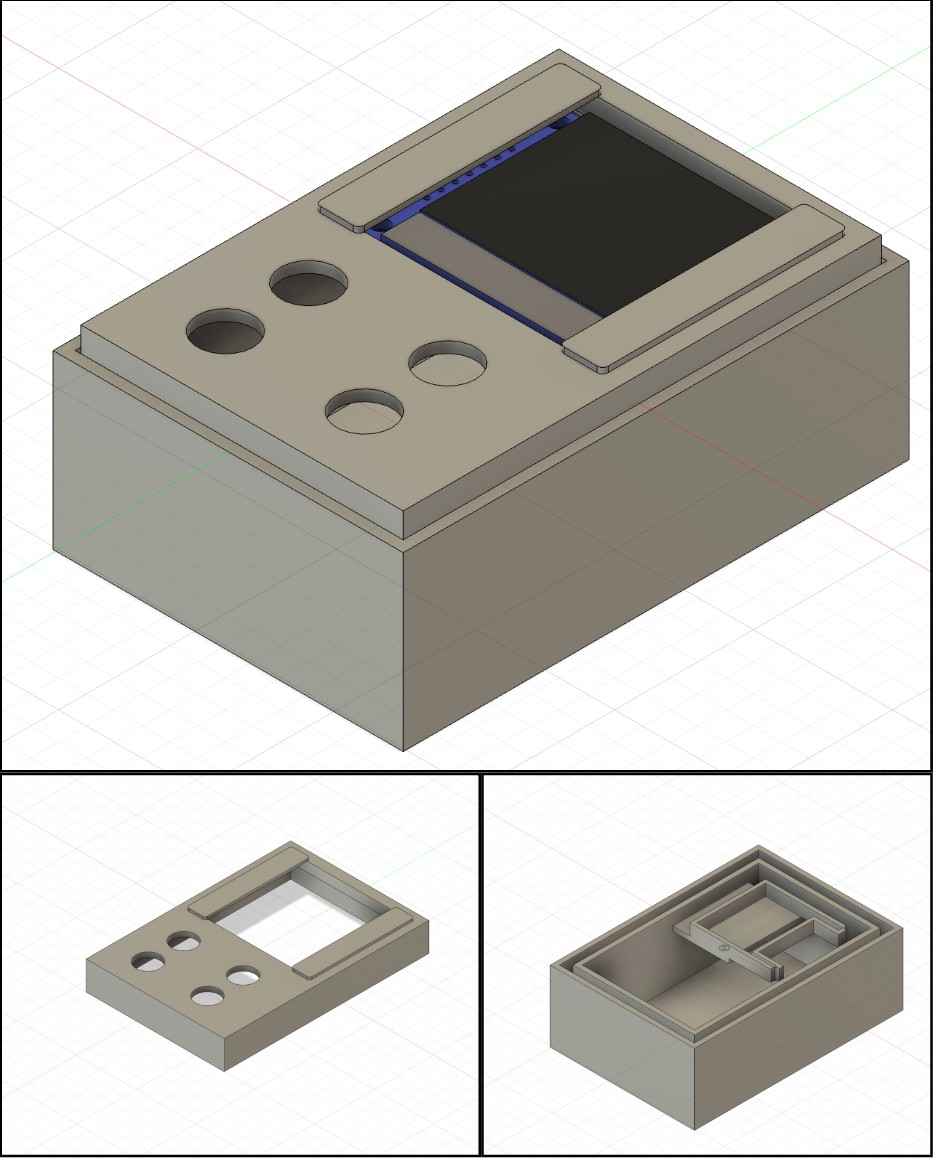

I was completely new to 3D modeling at the beginning of this week, and I redesigned the model multiple times throughout the process. I chose Fusion 360 for 3D modeling because it provides an intuitive and powerful environment for parametric CAD, including sketch-based modeling, timeline history, and solid modeling tools suitable for fabrication.

I modeled my device in 3D, including the main body, screen housing, and four buttons, aligning the model with my earlier 2D designs. Through repeated iterations, I refined the dimensions and layout to ensure the design was both realistic and ready for physical production. I also used models from GrabCAD to represent electronic components and verify fit and clearance.

I began by creating 2D sketches for the top face of the device, defining the screen opening and button cutouts. I applied sketch constraints such as equal spacing, coincident points, and fixed dimensions to keep the geometry consistent during edits. After completing the sketches, I extruded the main body and used the shell tool to create a hollow interior for electronics.

Although I explored the concept of user parameters during this week, I did not rely heavily on them in this design. Most dimensions were defined directly in sketches, as the geometry was relatively simple and did not require frequent global changes. Parameters were therefore not necessary to maintain flexibility at this stage.

Next, I imported the downloaded GrabCAD models of the screen and buttons and scaled them appropriately to match the real components. I positioned these parts using the assemble → joint feature to verify alignment and clearance. I added fillets to corners and button housings to improve both aesthetics and ergonomics, and included internal support features to better secure the screen during assembly.

Note: I did not build a full assembly structure or rely on advanced assembly constraints, as the design consists of a single main body with minimal moving or interdependent parts. Using separate assemblies or complex constraint schemes would not have added meaningful value at this stage and would have introduced unnecessary complexity.

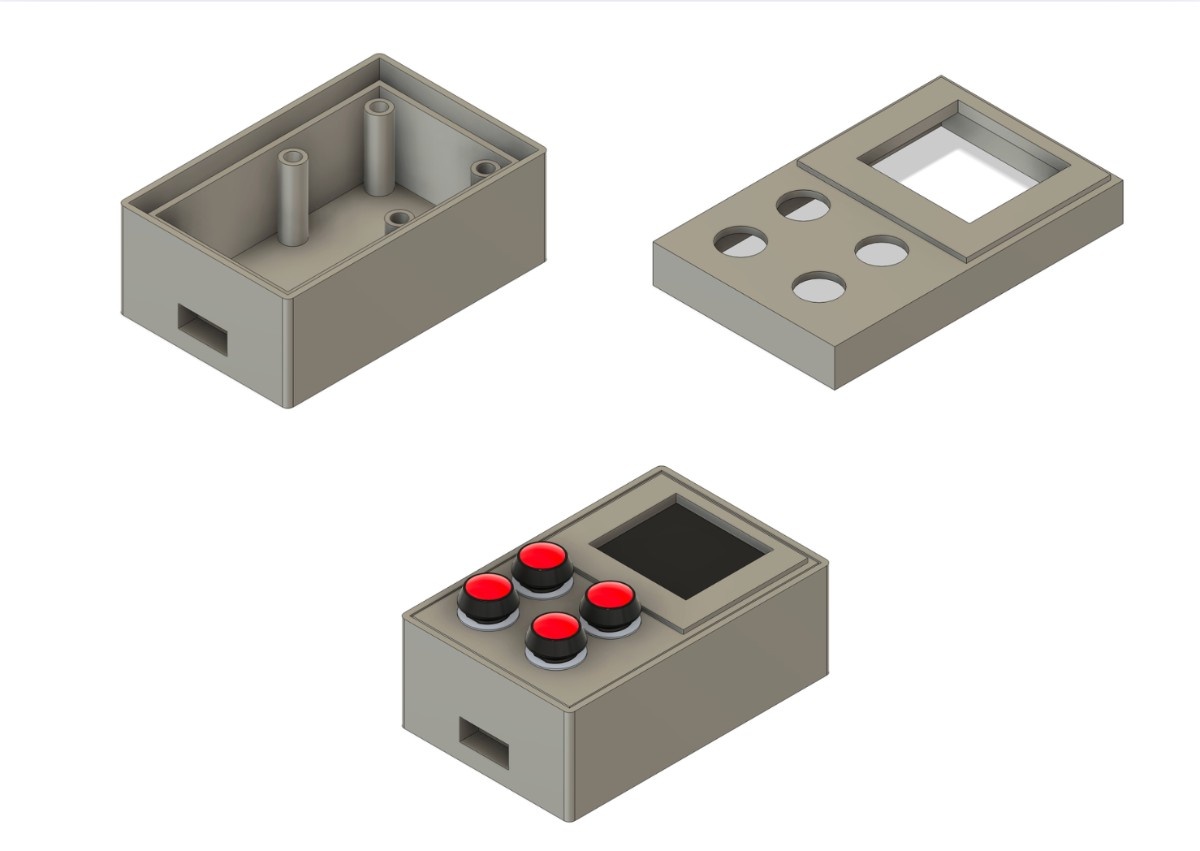

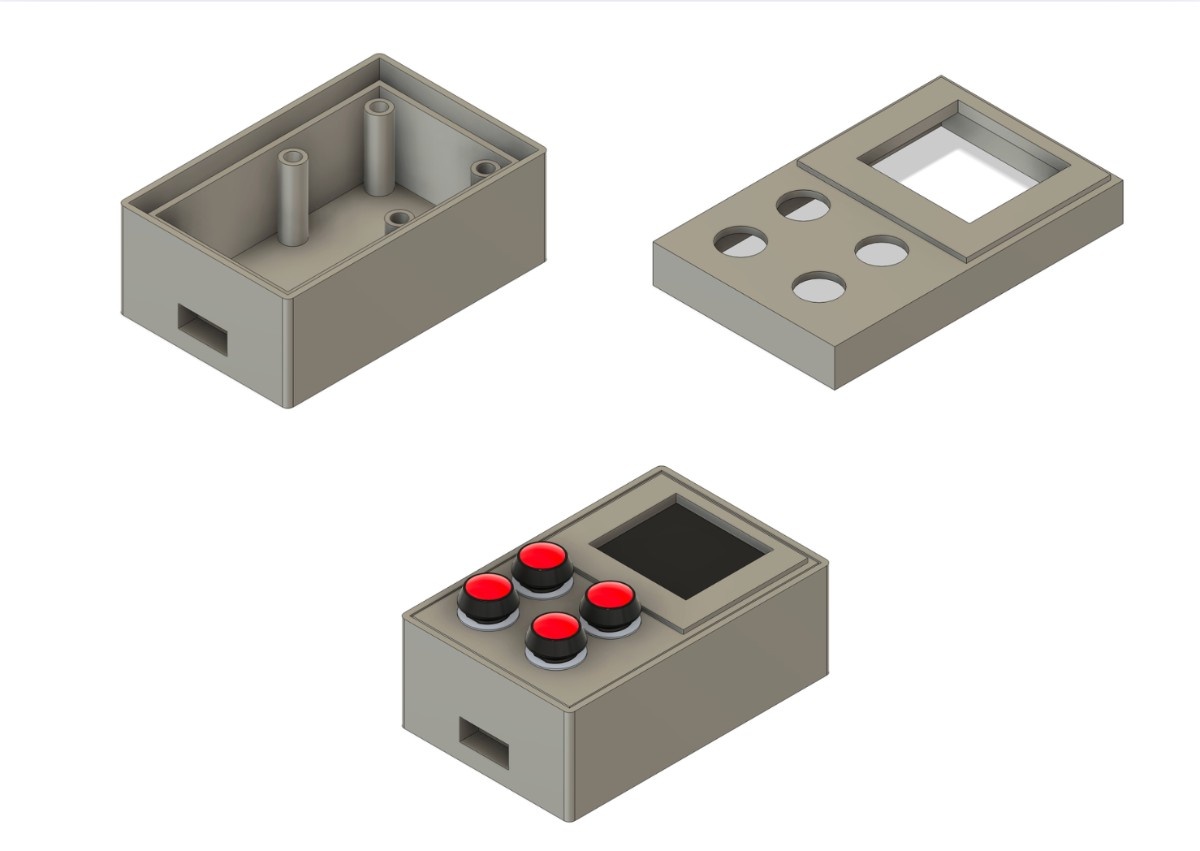

The final 3D model represents a compact device body with a recessed screen area and four tactile buttons arranged in a grid layout. Rounded edges, internal clearances, and mounting features were incorporated to ensure the design is suitable for 3D printing and physical assembly.

I exported the final model in both .f3d and .stl formats — .f3d for future parametric edits and .stl for slicing and 3D printing.

Here you can see the design process using the Fusion 360 timeline tool:

Here you can see my v1 hero shot:

After printing and receiving feedback, I made several changes to the design. The original screen holder was impractical, so I redesigned it as four cylindrical supports extending from the interior base. Some dimensions also required adjustment because the GrabCAD models did not perfectly match the real components. Additionally, I added a 0.2 mm tolerance to account for 3D printer accuracy.

Below is the final version of the design after these revisions:

Below is the complete timeline showing the full design process from start to finish:

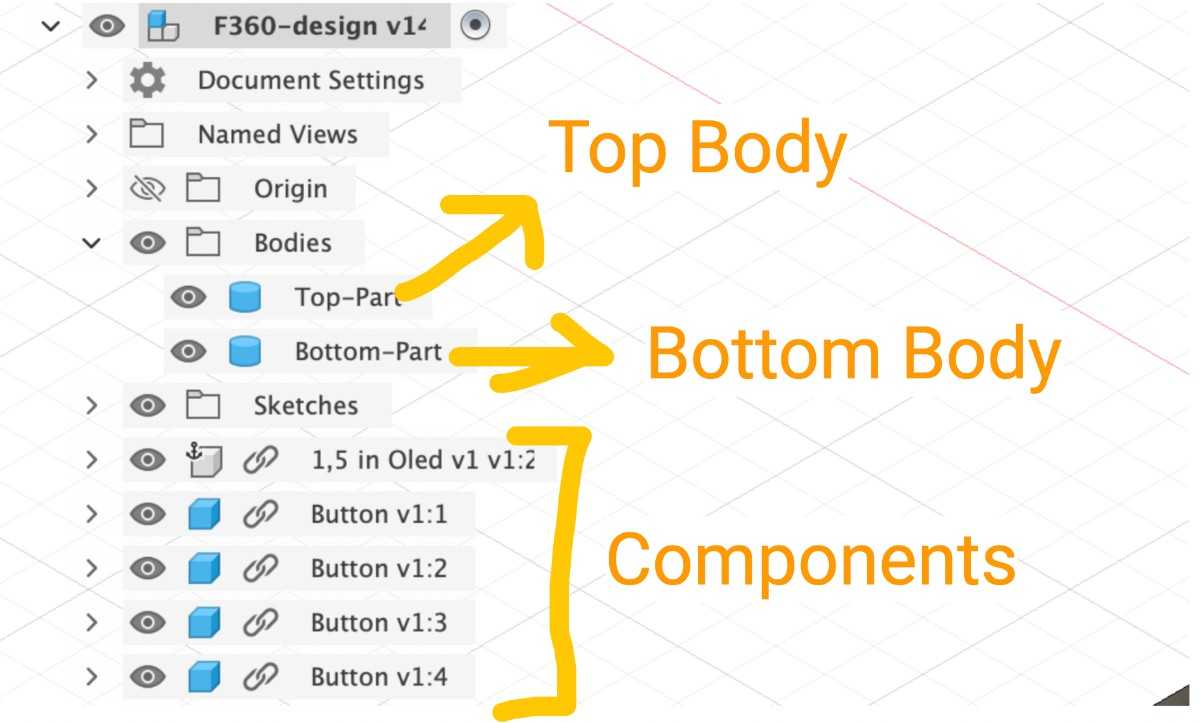

Below is the layers of the Fusion 360 design of my possible final project:

3D Animation

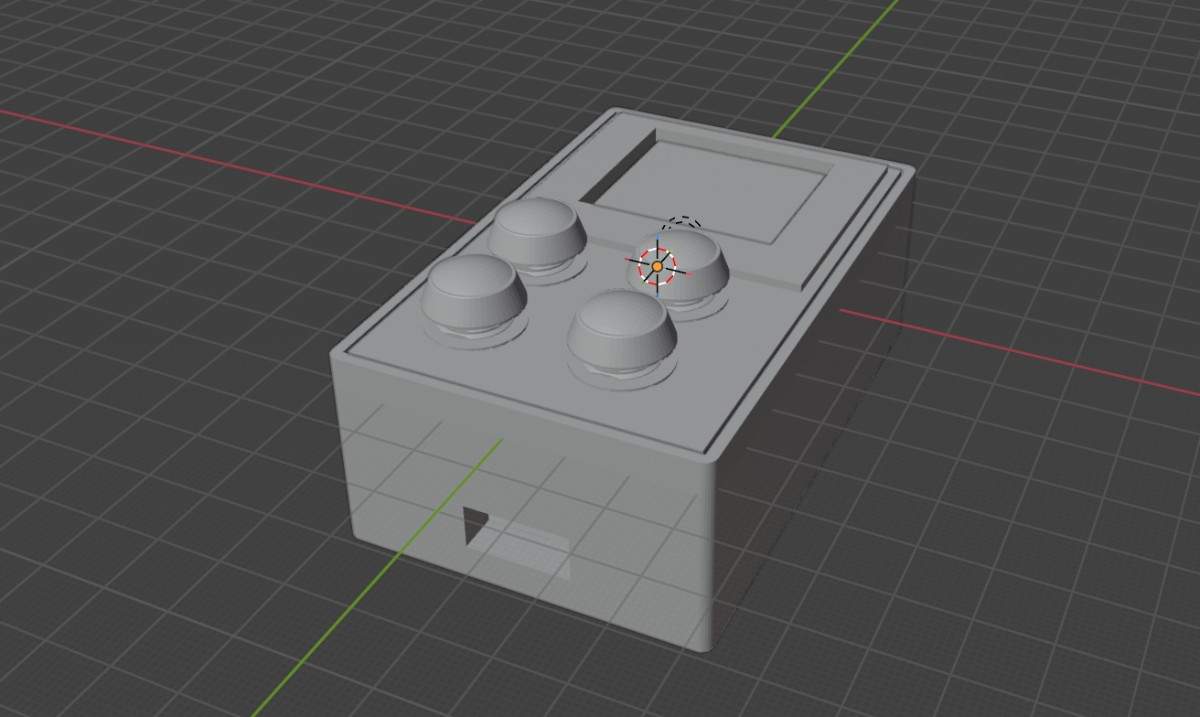

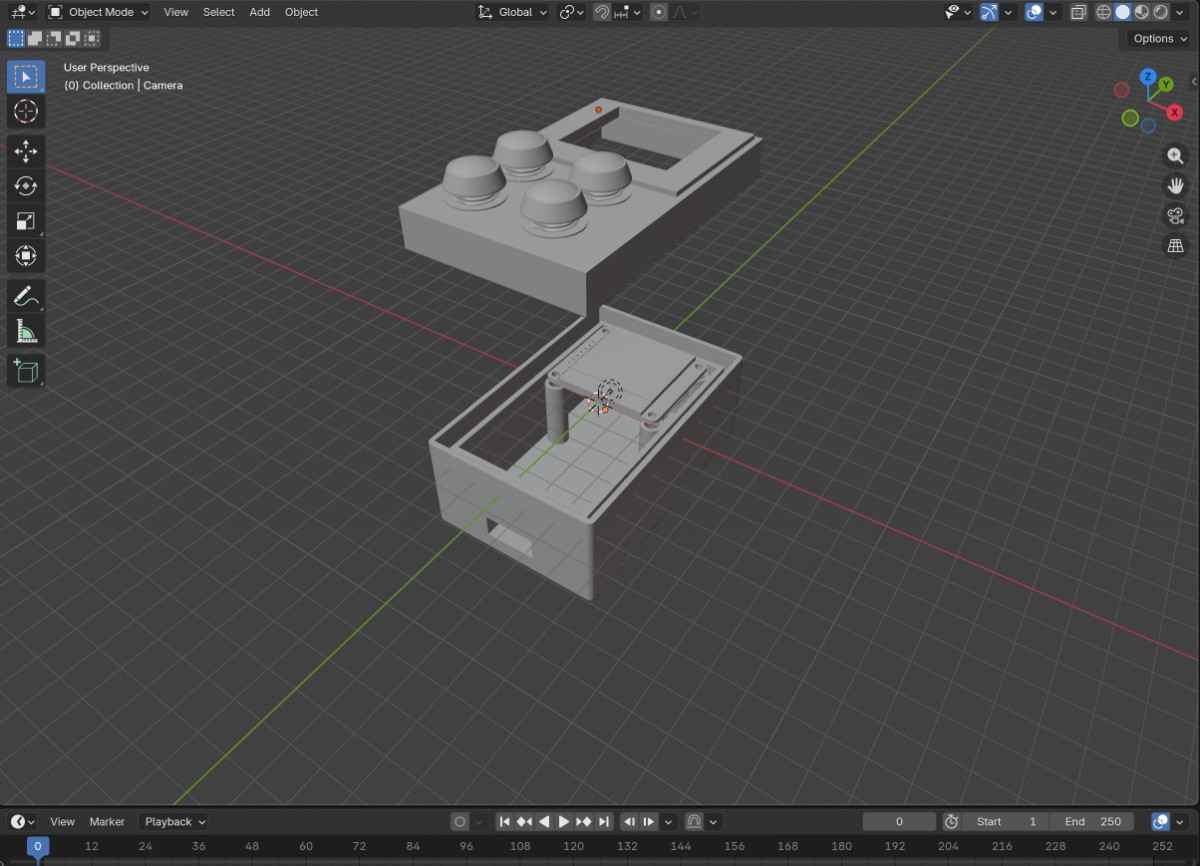

In addition to parametric modeling in Fusion 360, I also used Blender to explore basic 3D animation workflows. Instead of redesigning the model, I imported my final Fusion 360 design into Blender and focused on visualizing the assembly process through animation.

The model was exported from Fusion 360 and imported into Blender as two separate parts. This allowed me to animate how the device comes together rather than only presenting a static final model.

Below you can see the imported model in Blender in its assembled state:

Below you can see the same design with the two parts separated before animation:

I created the animation using keyframe-based animation. By defining the position and rotation of each part at different frames on the timeline, I animated the two parts moving smoothly into place. This helped me understand Blender’s timeline, transformation tools, and basic animation workflow.

The animation represents the assembly sequence of the device rather than a physical simulation, making it useful for communicating how the design is structured and how components relate to each other.

Below you can see the final rendered animation:

The original .blend file was saved alongside the design files to preserve the full animation timeline and ensure reproducibility.

Media Compression

All images and videos used in this documentation were compressed before uploading to ensure fast loading times and to keep file sizes reasonable without sacrificing clarity.

For images, I used an online image compression tool to reduce file sizes while preserving visual detail. Each image was manually checked after compression to ensure that important design features, edges, and text remained clearly visible. The compressed images were then exported in .jpg format and used directly in the documentation. Tool used: https://image.pi7.org/compress-image-to-50kb

For videos, I compressed the original screen recordings and renders using an online video compression tool. The resolution was preserved while reducing bitrate and file size to make the videos suitable for web embedding. All compressed videos were tested in the browser to confirm smooth playback and acceptable visual quality. Tool used: https://www.freeconvert.com/video-compressor

This compression step was essential for maintaining a lightweight documentation page while still clearly communicating the design process and outcomes.

What I Learned

This week helped me understand that CAD is not a single tool or skill, but a workflow that changes depending on intent.

I learned that:

- Raster-based tools are best suited for early-stage ideation and visual planning, but should not be used for fabrication.

- Vector-based tools act as a bridge between design and manufacturing, where every line and shape has physical meaning.

- Parametric 3D CAD enables iterative design, allowing geometry to be refined as constraints, tolerances, and real-world feedback are introduced.

Working with Fusion 360 taught me the importance of sketch constraints, dimensional intent, and timeline-based modeling. I also learned that not every design benefits from heavy parameterization — simplicity and clarity can be more effective when geometry is stable.

By importing real component models and adjusting tolerances after printing, I experienced how digital models rarely match reality on the first try, and how iteration is a core part of digital fabrication. Using Blender for animation further helped me see CAD models as communication tools, not just fabrication files.

Overall, this week shifted my mindset from “drawing shapes” to designing systems that can be manufactured, assembled, and iterated on.